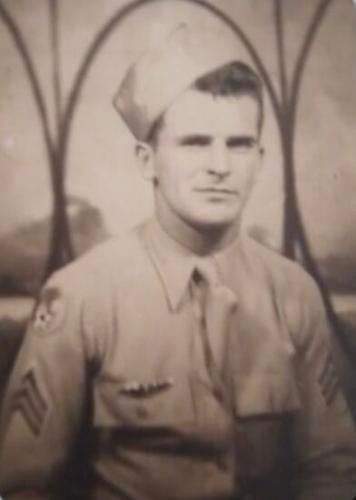

It was 1944 and Daisy Stevens Franklin was just 18 months old when her father, Staff Sgt. Henry L. Stevens had to leave his family behind as he served in WWII. Stationed in France – he was a gunner and engineer aboard a B-26F “Marauder” aircraft, nicknamed Shirley D.

Late that year, Stevens 23, was assigned to the 557th Bombardment Squadron, 387th Bombardment Group, Ninth U.S. Air Force, in the European Theater of Operations.

On Dec. 23, 1944, the plane was shot by anti-aircraft fire over Bitburg, Germany as they returned from a bombing raid. Witnesses reported that the Shirley D took damage to the right engine, resulting in a massive fire which forced crewmen to bail out. Survivors watched the plane crash near Winville, Belgium, with several crewmembers, including Stevens, still onboard. Four of the crewman parachuted out, but Stevens, the pilot and co-pilot were killed in the crash.

While the remains of some of the seven-member crew were recovered soon after the crash and others years later, Stevens’ remains were not recovered until last year. Mrs. Franklin is 80 years old.

Even though she grew up knowing that her father had been in the military and killed in the crash that day, he was always just “dad” she said. It wasn’t until she was much older that she learned he was a hero. She said the family would share stories about her dad and he enjoyed joking around and was easy to show his affection.

“When I was about 12, I had questions.” She spoke with one of her cousins who had gone in the military with her dad – asking how it happened and wondering what happened it he escaped the crash and what if he was living somewhere with amnesia?

“At that age you wonder about those kinds of things,” she said.

“Everybody that ever talked to me assured me,” she said, adding that it wasn’t until those later years that she learned he went forward to help the pilot stabilize the plane, because the co-pilot was injured.

“He could’ve gotten off, he could have bailed, but he didn’t,” she said, noting that while it hurts, it also “… gives me pride in the fact that he was willing to do that for his fellow pilots – he put their lives before his. That’s the most honorable thing a person can do.”

“I didn’t know any of those things back then.”

She said there were two explosions – one when the plane was hit and another when the plane crashed. Finding her father’s remains was a challenge and ended up taking decades, through the work of various groups.

She said her mother was working as a server at a drive-in restaurant in Palmetto, when her parents met. He and his buddies were stationed in the area, training at McDill Air Force Base and Avon Park.

The building is still standing, but it’s no longer a restaurant, she said.

“They went skating - they both liked to skate. They went to the movies,” she said.

After about four months, they got married, noting that her dad had trained in several different locations. She said when he was stationed overseas, she and her mom stayed with her grandmother on her mother’s side. Her dad’s mom would come down from Louisiana to visit. His dad was also in the military. Franklin said a national magazine had even written an article on her father’s family – his mother had taken in his son from a previous marriage.

“It was very difficult, but by the time I was 18 or 20, I had reconciled myself to it,” she said of knowing her father had been killed.

And then, into her thirties, when “I felt like I had put all of that aside and … I had put it aside. But, when they called me,” she said of the additional searches for her father’s remains. They asked for a sample of her DNA, thinking there wasn’t much of a chance for a match.

She eventually got a phone call telling her they believed they had identified her father’s remains.

She said it was “rather emotional,” especially the service where his remains were returned to the United States this past week.

“I really had wanted closure for so long. I had accepted that I was never going to have full closure,” she said, adding that there are a couple of things that she would have liked to have happen. She said she would have liked for his mother to know – she has since passed; and, she is sad that, “… he never got to see me grown and married. He never got to know his grandson.” And that she didn’t get to see him in the autumn of his life.

She said she knows there are a lot of people who don’t get to see that and she feels very grateful and blessed for all she has, noting the “… number of bodies that still haven’t been recovered other there.”

“I’m very, very grateful. When I look at the book they gave me on him, and the archeological teams that gave of their time,” she said, adding there have been so many involved in the recovery.

Having believed she had put things behind her, she said, “I thought It would be less emotional.”

Earlier this week, she was selecting songs, starting with “I’ll Fly Away.”

She said she cried through, “… every song, I must have listened to 10 or 12 songs.”

Mrs. Franklin also takes pride in her family and their patriotism, their willingness to serve, noting that several of her family members have been in the military.

She said she also thinks about how things were then – what she faced at the same age… what her son faced at the same age.

“We never had those kind of life-changing decisions that you had to make,” at that age, she noted.

While she experienced losing her father at a young age – she also lost her first husband early in her marriage – he was killed in an accident on the military base, she said.

They had only been married three months.

Mrs. Franklin has letters written from her parents to each other, while he was away. They include phrased endearments like “My darling,” and news that had been blacked out to keep his location safe.

She said her father sent her mother a beautiful set of postcards – with hearts and service men and women on them and made from a pink, plastic-like material.

“Very sweet,” she said, adding that she had them framed and hanging in her home at one time, to keep something of his.

Franklin said she was a couple of years old when her mother remarried. Once again, military was a priority – her stepfather was in the U.S. Navy.

“He was a wonderful stepfather,” she said, adding that through that union, two boys were born.

She said she feels very fortunate to have had the family she had.

Friday Service to honor Stevens in Bushnell

The public is invited to help honor WWII hero U.S. Army Air Force Staff Sgt. Henry L. Stevens on Friday, March 8 at the Florida National Cemetery in Bushnell.

There will be a motorcycle escort from Bushnell to the Florida National Cemetery, but for those who unable to join the escort, they can stand along the side of S.R. 48 in Bushnell, between U.S. 301 and Hayes Road or along C.R. 476 and C.R. 476 B on the route to the cemetery at approximately 12:30 p.m.

Those supporting the effort are encouraged to bring American flags and let the family know that the Stevens’ sacrifice is being honored. The public is also invited to go directly to the cemetery to attend the 1 p.m. interment service at the Assembly Area. Those who attend are encouraged to arrive by noon, but no later than 12:40 p.m. A flyover is planned during the service.

While the remains of some of the seven-member crew were recovered soon after the crash and others were recovered years later, Stevens’ remains were not recovered until last year.

A few days after the crash, several Belgian residents recovered one set of remains from the crash site near Houmont and turned them over to American forces operating in the area. American Graves Registration Service (AGRS) personnel initially identified the pilot, while the other set of remains remained Unknown. By Dec. 26, 1944, everyone from Stevens’s aircraft had been identified and accounted for except for Stevens, and he was declared non-recoverable.

In 2013, DPAA personnel returned to the crash site near Winville, Belgium, where they recovered materials associated with the crashed B-26. Later in 2019, while working in conjunction with researchers from the University of Wisconsin, possible remains were located and sent to the DPAA laboratory for testing and possible identification.

To identify Stevens’s remains, scientists from DPAA used anthropological analysis. Additionally, scientists from the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System used mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and autosomal DNA (auSTR) analysis.

Stevens’s name is recorded on the Tablets of the Missing at the Ardennes American Cemetery, an American Battle Monuments Commission site in Neupré, Belgium, along with others still missing from WWII. A rosette will be placed next to his name to indicate he has been accounted for.